Central Insights:

- The method by which the root of lust, anger, etc., can be destroyed.

Key Points:

- The soul should deeply imbibe a sense of aversion toward sensory pleasures and kamadik (vices like lust, anger, etc.).

- Even if one possesses understanding, one should avoid weak places, times, or circumstances.

Explanation:

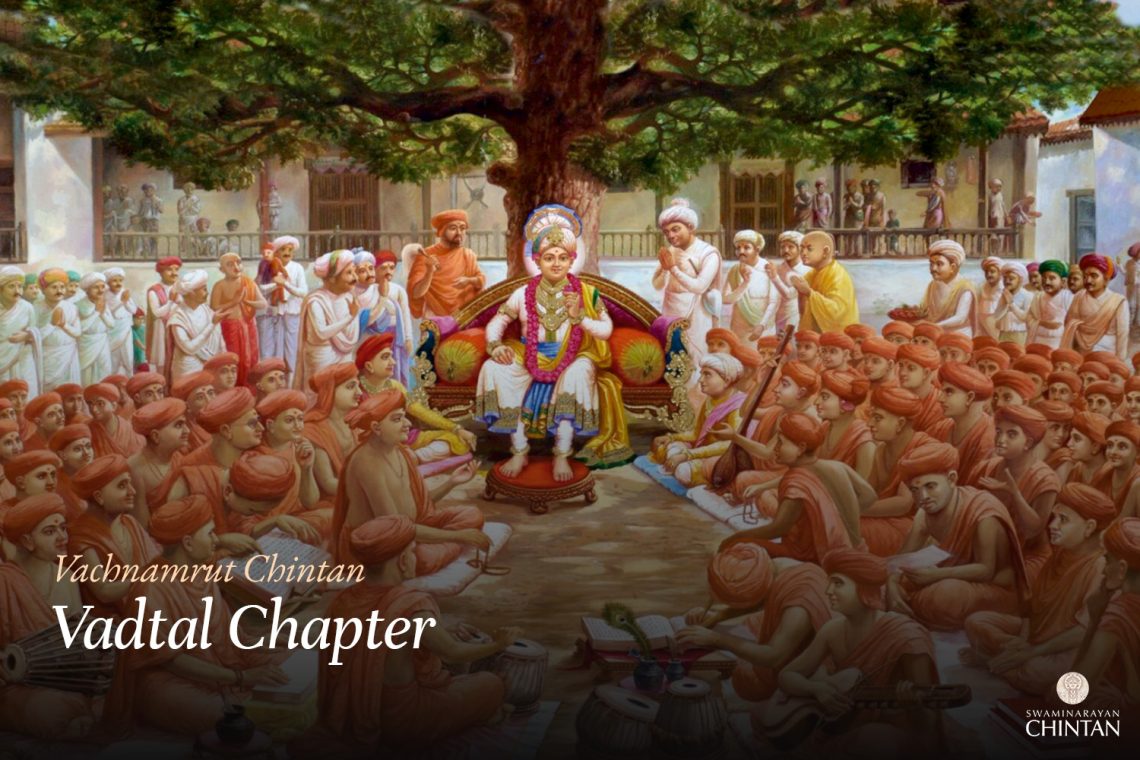

In this Vachanamrut, Shreeji Maharaj asks the paramhansas a question. He explains that rajogun (passion and activity) is the source of lust, while tamogun (darkness and ignorance) is the source of anger and greed. He then poses a question: What is the one method by which the root of kamadik (lust and other vices) can be destroyed, so that these vices do not resurface in the form of desires or actions? Shukmuni responds, saying that the root of kamadik in the heart is destroyed only when one enters nirvikalp samadhi (a state of transcendental consciousness without self-awareness) and experiences atma darshan (Self-realization).

Shreeji Maharaj then raises a doubt: Were not Shiva, Brahma, Shrungi Rishi, Parashar, Narad, and others capable of experiencing nirvikalp samadhi? (Were they not Self-realized?) Despite this, when their senses aligned with worldly desires, they too succumbed to lust. Thus, while they had attained nirvikalp samadhi, when the natural course of their senses aligned with worldly objects, they were disturbed by kamadik. Therefore, Shukmuni’s answer does not fully address the question.

Further, Shreeji Maharaj explains that a jnani (person of knowledge) remains unaffected by kamadik while in nirvikalp samadhi, just as an ignorant person remains unaffected during deep sleep. However, when their senses naturally engage with the world, both the jnani and the ignorant are disturbed by kamadik. Thus, there appears to be no special distinction between the jnani and the ignorant in this regard. He then invites other paramhansas to answer. Despite the attempts of learned santos, none can satisfy Shreeji Maharaj.

Then, Shreeji Maharaj says that, unlike the others, King Janak followed the pravrutti marg (path of action) while remaining unaffected by worldly influences. He recounts that once, a renunciant named Sulabha, who was a disciple of the sage Panchshikh, approached Janak in his court with the intent to test him. Though she displayed gestures and tried to attract him, Janak remained entirely undisturbed. Sulabha even entered Janak’s consciousness, but he was not swayed, holding his ground unwaveringly. Only after her repeated prayers did he permit her to leave his consciousness. Exhausted and defeated, Sulabha realized Janak’s steadfastness. At that point, Janak explained to her, “You are attempting to entice my mind, but my guru, Panchshikh Rishi, has blessed me with the knowledge of Sankhya and Yog.”

Janak continued, explaining the essence of Sankhya as the understanding of the twenty-four elements and the realization of their inherent flaws. Sankhya teaches one to instill deep aversion in the soul for worldly objects and the five senses. The practice of Yog, he said, cultivates detachment and an understanding of the attributes of the supreme God. By realizing both, Janak explained, he had gained the awareness that happiness and sorrow are equal and that the so-called pleasures of the world are, in fact, forms of suffering. Thus, even if his kingdom of Mithila were to burn, he would remain unaffected, for nothing of his true self would be harmed. In this way, he remained actively engaged in the world, yet unaffected. Such was Janak’s response to Sulabha, which ultimately impressed her. He was also recognized as the guru of atma nishta (Self-realization) by great sages like Shukdevji.

Here, one must reflect on why Shreeji Maharaj esteemed Janak higher than even Brahma, Shiva, Parashar, and others regarding detachment from flaws and remaining unaffected by vices. Were they not capable of nirvikalp samadhi? Were they not as Self-realized as Janak? Indeed, they were; moreover, Brahma and Shiva are considered the very sources of knowledge. The Sankhya and Yog knowledge Janak possessed was certainly not unknown to Brahma and Shiva, nor did they lack it.

The reason Janak was esteemed higher was due to his extraordinary resolve to root out all awareness of the flaws of the elements and sense-objects. He had firmly established within his soul a deep aversion to kamadik and had embraced the challenge of remaining unaffected by vices, even while engaged in worldly action. In knowledge, Sankhya, and Yog, Brahma and Shiva surely surpassed Janak. However, Janak’s unwavering resolve to reject flaws and maintain detachment in his soul was what set him apart.

Shreeji Maharaj then clarifies that one whose understanding is firm like that of Janak, with a deep aversion toward panch vishay (the five sensory objects) and kamadik as enemies, will not succumb to vices in any situation. Even if such a person’s senses naturally engage with the world, they will not be disturbed by kamadik. Whether a devotee is a renunciant or a householder, if his understanding is deeply rooted, the seed of kamadik is eradicated from his heart. Thus, there is no distinction between a householder and a renunciant—only the depth of understanding matters.

In conclusion, Shreeji Maharaj points out that of the many renowned sages, some lack the firm understanding of Janak, while others succumbed to adverse places, times, and circumstances. Therefore, even with firm understanding, one should avoid all forms of kusang (association with evil influences) and never indulge in weak places, times, or circumstances. This is the only way to ensure that the seed of kamadik does not grow.

Glossary

| Kamadik – Lust, anger, etc. The internal enemies (lust, anger, greed, attachment, ego, and envy) that disturb spiritual progress. |

| Rajogun – Mode of passion The quality associated with activity, desire, and attachment. |

| Tamogun – Mode of ignorance The quality associated with laziness, delusion, and lack of clarity. |

| Nirvikalp Samadhi – A state of perfect absorption or concentration where the mind is undisturbed It is a state of meditation where the individual’s mind is fully absorbed in the object of meditation, without any distractions, and free from worldly attachments. |

| Atma darshan – Self-realization The realization of one’s true self (Atma), distinct from the body and mind, typically achieved through deep meditation and devotion to Bhagwan. |

| Pravrutti Marg – The path of worldly involvement |

| Nivrutti Marg – The path of renunciation |

| Sankhya – A school of philosophy A philosophical system that explains the nature of the soul and the universe, emphasizing the distinction between the soul (Atma) and the material world. |

| Yog – Union or spiritual practice A philosophical and practical discipline aimed at achieving union with the divine through meditation, control of senses, and spiritual focus. |

| Panch Vishay – Five sensory objects |

| Kusang – Evil Association Association with individuals or ideologies that destroy faith in Bhagwan and devotion. |