Central Insights:

- The principles of Sankhya and Yog.

Main Points:

- Sankhya philosophy: Without transcending the 24 elements of Maya, liberation cannot be attained.

- Yog philosophy: Without fully controlling the senses and Antahkaran within Paramatma, liberation is not possible.

Commentary:

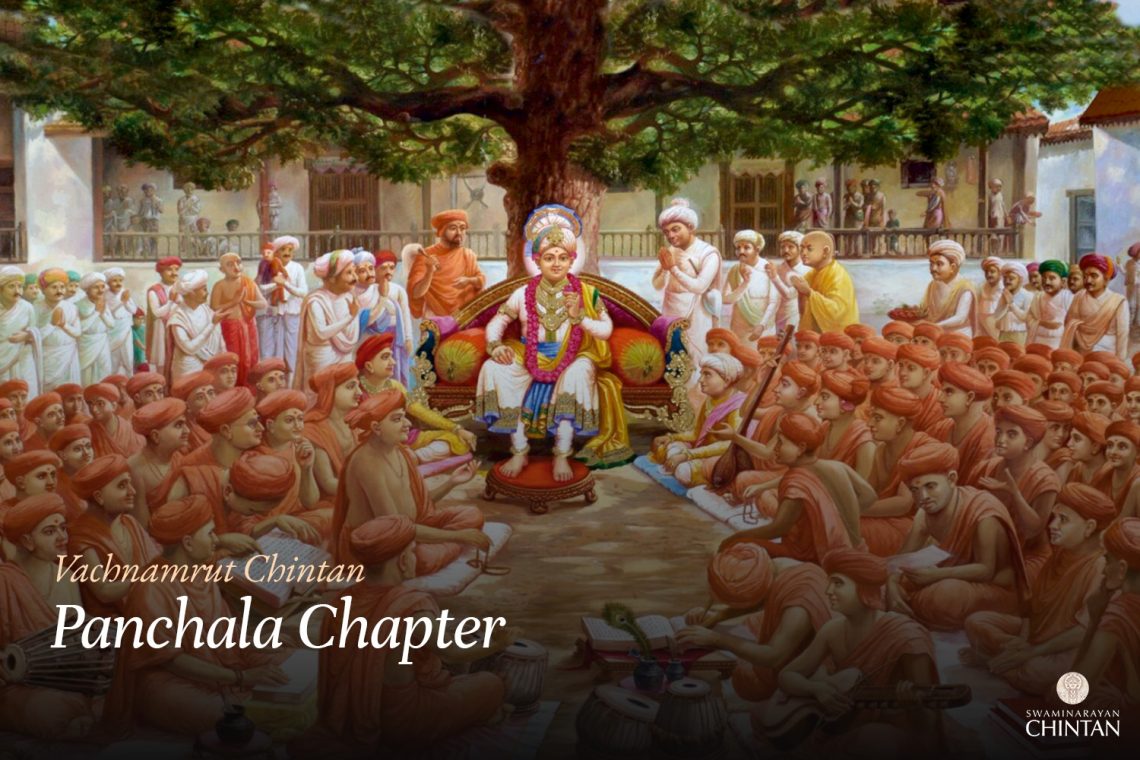

In this Vachanamrut, Maharaj begins by saying, “Bring the Moksha Dharma scripture, and let’s discuss the chapters of Sankhya and Yog.” After the scripture was brought, Nityanand Swami started reading. Maharaj then elaborated on the hidden meaning, saying that in Sankhya, Paramatma is considered to be the 25th element, whereas in Yog, He is the 26th element. In Sankhya, Jeev and Ishwar are counted within the 24 elements. However, in Yog, Jeev and Ishwar are regarded as distinct from the 24 elements right from the beginning. The followers of Yog believe that no matter how much one contemplates the difference between the soul and the non-soul (i.e., the body), without the refuge of the manifest God, Moksha cannot be attained. On the other hand, the followers of Sankhya believe that only by transcending the 24 elements of the body and mind can Moksha be achieved.

Maharaj accepted the unified view of both philosophies. According to Sankhya, when a Jeev becomes Brahmrup (identifying oneself with Brahm), only then is the instruction of Yog applicable. In support of this, Maharaj quoted the verse:

ब्रह्मभूतः प्रसन्नात्मा न शोचति न काङ्क्षति |

समः सर्वेषु भूतेषु मद्भक्तिं लभते पराम् ||

brahmabhūtaḥ prasannātmā na śocati na kāṅkṣati |

samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu madbhaktim labhate parām ||

(Gita 18.54)

आत्मारामाश्च मुनयो निर्ग्रन्था अप्युरुक्रमे |

कुर्वन्त्यहैतुकीं भक्तिमित्थंभूतगुणो हरिः ||

ātmārāmaśca munayo nirgraṇthā apyurukrame |

kurvanty-ahaikīṁ bhaktim-itthaṁ-bhūta-guṇo hariḥ ||

(Bhagwat 1.17.10)

परिनिष्ठितोऽपि नैर्गुण्ये उत्तमश्लोकलीलया |

गृहीतचेता राजर्षे आख्यानं यदधीत्तवान् ||

pariniṣṭhito’pi nairguṇye uttamaśloka-līlayā |

gṛhīta-cetā rājarṣeh ākhyanam yad-adhītavān ||

(Bhagwat 2.1.9)

Additionally, Maharaj discussed that both philosophies have certain flaws. In Yog, the flaw lies in identifying Jeev and Ishwar as the 25th element and equating both of their bodies with the 24 elements, thus suggesting a state of equality between them. This results in a flawed view that Jeev and Brahma are equal, which is not the case. To resolve this, one must understand that while the elements in the body of a Jeev are limited, the elements in the body of Ishwar are Mahabhoot (the primary elements). Thus, Jeev and Ishwar are not the same. Jeev is knowledgeable, while Ishwar is filled with divine glory. Therefore, they are not equivalent.

Moreover, there are differing views on how to meditate on Paramatma between the two philosophies. The Sankhya followers believe that रागोपहतिर्ध्यानम् — ‘rāgopahatir dhyānam’ removal of attachment from the chhoviṣ (24 tattvas) and the material Panch Vishay (sensory objects)—is meditation. In contrast, the Yog followers’ view is that प्रत्ययैकतानता ध्यानम् — ‘pratyayaikatanatā dhyānam’—a continuous flow of remembrance focused on the Murti (divine form) of Ram, Krishna, and other incarnations—is considered meditation. Since the Sankhya philosophy does not fully accept the form of Paramatma, it defines meditation merely as the removal of attachment.

The harmonious resolution between the two is that the mind naturally focuses intensely on what it is attached to. Therefore, after detachment is achieved, the mind should concentrate single-mindedly on the Murti of Paramatma, allowing meditation to be accomplished with ease and happiness. However, the flaw in the Sankhya system is that by labeling all forms as false, they also consider the avatars and Murtis of Bhagwan to be unreal. To correct this, one must understand that everything born from Prakruti is indeed false, but the form of Bhagwan is the ultimate truth, and one should meditate upon it. According to Yog, focus must be placed on a single point of concentration, but this can introduce the flaw of seeing Bhagwan as limited or divisible, which must be avoided.

The primary aim of the Sankhya philosophy is to become free from the threefold miseries. By considering the material elements as mithyā (false) and understanding oneself to be separate from them, the goal is achieved by severing all connections with the 24 tattvas (elements).

On the other hand, the aim of the Yog philosophy is also the same: हेयं दुःखं अनागतम् — heyaṃ duḥkham anāgatam to prevent future misery. However, the method is different. They believe that by controlling one’s vṛutti (tendencies) from harmful objects and focusing one-pointedly on the blissful object, which is Paramatma, suffering is eliminated. Thus, the reconciliation between the two is that by detaching from māyik (material) objects and connecting with Bhagwan, suffering is eradicated. In this way, Maharaj explained several techniques, demonstrating how both paths can be harmonized and used in the pursuit of liberation.

Glossary

| Sankhya – A school of philosophy A philosophical system that explains the nature of the soul and the universe, emphasizing the distinction between the soul (Atma) and the material world. |

| Yog – Union or spiritual practice A philosophical and practical discipline aimed at achieving union with the divine through meditation, control of senses, and spiritual focus. |

| Moksh Dharma – A scriptural text A section of the Mahabharat discussing paths of liberation including Sankhya and Yog. |

| Paramatma – Supreme God God, the all-pervading and ultimate reality. |

| Ishwar – God |

| Brahmrup – Oneness with Brahman (God) |

| Mithya – False or unreal The concept in Sankhya philosophy that the material world and its elements are false, in contrast to the eternal and true divine form of God. |

| Murti – Divine form of God |

| Brahmabhutah – State beyond maya A liberated state described in the Bhagavad Gita where one is free from desires and sorrows. |

| Nairguṇya – Beyond material qualities The pure state free from Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas; associated with Paramatma and the liberated state. |

| Mahabhoot – Primary elements The fundamental elements of creation, such as earth, water, fire, air, and ether, which form the material universe. |

| Vrutti – Mental tendencies or fluctuations The movements or fluctuations of the mind that lead to attachment or detachment from worldly objects and spiritual focus. |

| Avatar – Incarnation of God A divine descent of Bhagwan into the world in forms like Ram, Krishna, etc., not subject to maya. |