Central Insights:

- The form of nishthā coupled with God’s greatness.

Key Points:

- Living a life dedicated to God and His devotees, abandoning personal self-interest, is called nishthā (firmness and conviction).

- A person who does not wish to retaliate is considered humble.

- Even one who does not waver in the human-like activities of God is said to have nishthā.

- Sharp intellect does not contribute to the nishthā in God as much as faith, theism, and divine feelings do.

Explanation

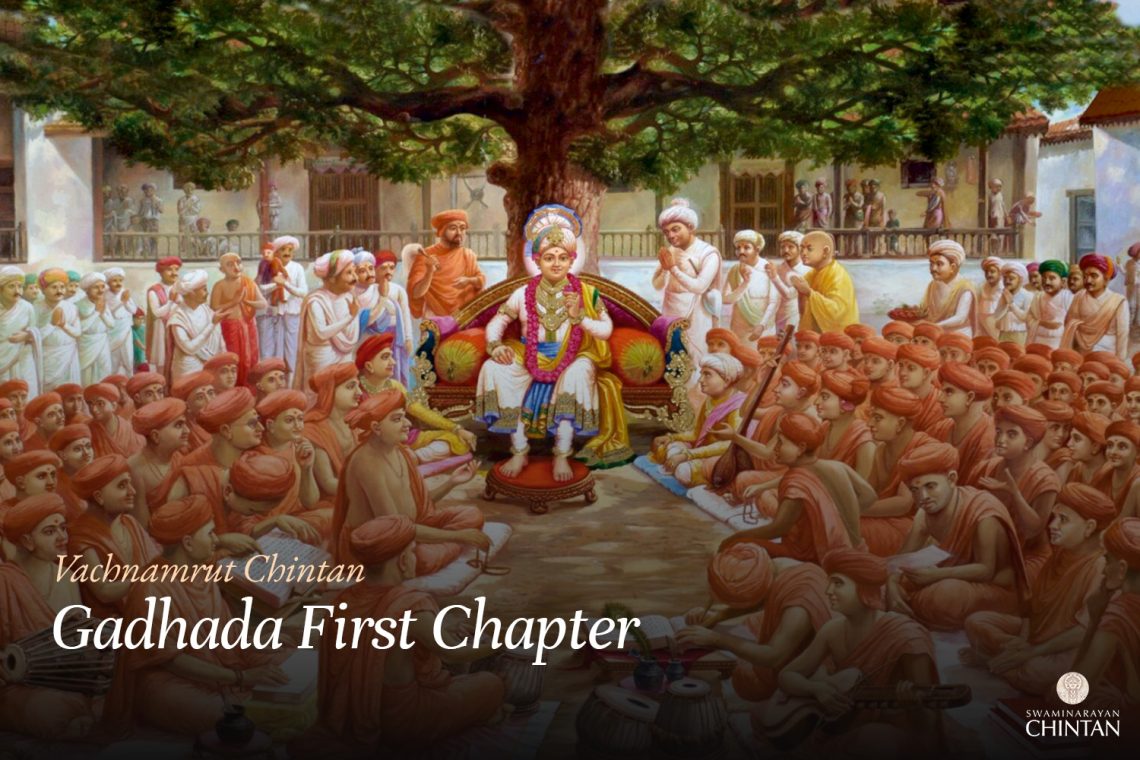

In this Vachanamrut, Muktānand Swāmi prayed to Mahārāj, saying that the previous day you had discussed a very profound matter with Dādā Khāchar, which we all wish to hear. Then, Shriji Mahārāj explained that a devotee who has firm nishthā (conviction) in the greatness of God and understands the greatness of saints and the fellowship, even if faced with severe karma and difficult times, these cannot harm the devotee. Conversely, if there is any wavering in the nishthā towards God and the saints, Mahārāj said that even if He tries to do good for them, He cannot succeed. This highlights the greatness of nishthā in God and His devotees.

In this context, Mahārāj has used the term nishthā. In the Sampradāy (sect), the term nishthā is highly revered and well-known. What does nishthā mean? The common meaning of nishthā is the absence of movement—cessation of movement—pause—until death, such meanings apply. With this understanding, in the Sampradāy, the term is used with a specific deeper significance. For instance, a naiṣṭhika brahmachāri (lifelong celibate) is one who vows to maintain celibacy until death. In the same way, the utmost dedication until death to God or to a devotee of God is called nishthā.

The goal is to live for God and die for Him. Among these two, dying is easier, but maintaining the goal throughout one’s life, living for that purpose, and dying while living for that purpose is called nishthā. Enduring the obstacles with a cheerful heart is also called nishthā. Mahārāj has said that a devotee who has nishthā towards God and the saints, even if faced with adverse times and karma, will not be affected. If there is any wavering in nishthā, even if we try to do good, it will not succeed.

Mahārāj placed greater importance on the nishthā (firmness or conviction) of His devotees than on Himself. If there is any fault in the dealings with God, it can be resolved by interceding through His devotees or by praying. However, if there is any mistreatment of a devotee, God does not rectify it. Thus, God values His devotees more than Himself, highlighting the greatness of nishthā towards saints and devotees.

Additionally, Mahārāj said that those who are humble should not be harmed in any way. Whether the humble person is a devotee of God or someone else, they should not be troubled even slightly. Harming a humble person is considered a sin equivalent to killing a Brahmin. The question arises: who is considered humble? The scriptures state that a humble person is someone who, even when wronged and capable of retaliation, does not wish to take revenge. If someone lacks material wealth, food, or clothing, the scriptures do not consider them humble. While the government might deem them poor, the scriptures only regard those with the above characteristics as truly humble.

Even if someone lives a life of hardship and lack, if their nature is peculiar, they are not considered humble. Conversely, a person who is prosperous and capable in every way, but does not harbor the desire for revenge, is considered humble. For example, in the story of Ambarish and Durvasa, Ambarish is considered humble. Similarly, in the tale of Ra’Mandlik and Narsinh Mehta, Narsinh Mehta is deemed humble. Titles like “Garib Nawaz” (Protector of the humble) or “Garib na Beli” refer to those who uplift such humble individuals, not those merely suffering from material lack. The latter are enduring the results of their destiny. In contrast, the truly humble person is considered a recipient of God’s grace. Therefore, one should never trouble such a humble person. Even if the accusations are true, the person causing trouble becomes a sinner.

Mahārāj says that committing an act of immorality with five types of women is considered a sin equivalent to killing a Brahmin. These five types of women are:

- One who has sought refuge to protect her virtue.

- One who does not wish to engage in relations on the day of a vow or fast.

- A faithful wife.

- A widow.

- A trustworthy woman. Engaging in immorality with these five types of women is considered as sinful as killing a Brahmin.

Then, when Muni began singing devotional songs about the Lord, Shriji Mahārāj remarked that when God incarnates for the welfare of living beings, He engages in activities just like humans. He experiences victory and defeat, fear, sorrow, lust, anger, greed, attachment, pride, jealousy, hope, and longing—just like human beings. Seeing these human-like actions, a true devotee finds joy and attains the highest state, while those who are opposed to God or are immature devotees see faults in these actions.

For example, the Rās Panchādhyāyī līlā (the wordely actions of God – a play) performed by God was of a purely worldly and romantic nature. God performed actions that would typically excite lustful men. Those without understanding of God’s greatness might get stimulated by hearing such līlās. However, Śukadevaji gloriously sang of these līlās, understanding their profound spiritual significance. He sang with great joy, recognizing the highly human characteristics of God. But when King Parīkṣit heard these same līlās, he became doubtful because he wondered how God, who came to establish righteousness, could engage with other women and break the dharma (righteousness). However, Śukadevaji, who understood the greatness of God, did not see this as a breach of dharma. He perceived that for such a great God, the concept of worldly senses and distinctions between male and female did not apply. God Himself resides as the inner controller within the hearts of women, so how could they be considered mere objects of desire? God, to subdue the pride of Kāma (the god of lust), who had previously vanquished all the deities, engaged in this līlā to challenge and ultimately humble him.

Just as a powerful king might supply weapons to his enemy and then go to battle with them, God provided Kāma (the god of love) with a conducive and stimulating environment. Despite this, He remained completely unaffected and shattered Kāma’s pride. Śukadevaji sang of these līlās understanding that such an ability belongs only to a supreme God. The gopīs, with whom God had these pastimes, also did not develop any faults. On the contrary, they realized that “Śrī Krishna is invincible; no other man can compare.” However, Parīkṣit saw faults due to his lack of understanding. Therefore, Śukadevaji is considered the guru of all paramahansas because he sang of the divine and joyous exploits of the Supreme Being. Even a paramahansa should sing of God’s divine exploits without harboring any faults and becoming opposed to Him.

The greatness of God is such that countless universes exist within each of His pores. When such a great God takes a human form, it allows living beings the opportunity to serve Him. If He remained solely in His vast form, even deities like Brahma would be unable to have His darshan or serve Him. Just as the fire of the submarine volcano remains in the ocean, but if it were to come into our homes, it would not be pleasant but destructive; however, when that same fire is in the form of a lamp, it provides comfort. Similarly, when God takes on a human form and appears manageable, it brings about the well-being of living beings. If He remained in His vast form, living beings would not even be able to have His darshan.

God assumes a human form and performs human-like activities so that living beings do not feel distant and can come closer to Him. If a soul is divine, it develops affection for God and recognizes Him. Therefore, faith, divine qualities, and devotion are essential for recognizing God. Endeavors, sharp intellect, deep study of scriptures, or cleverness do not aid in recognizing God. Sometimes these qualities can even be obstacles in approaching God or great souls. Not always, but if faith and other such qualities are lacking, these can become obstacles, as shown in the history of the scriptures.

The gopīs were not scholars of the scriptures, whereas Śukadevaji was a master of the scriptures. Uddhavaji excelled in wisdom. What all of them had in common was divine feelings and faith. They perceived the divine nature in God. In contrast, learned individuals like the Brahmins of Vraj, kings like Shishupāla, and others lacked faith and trust, leading them to see God in a human way and with inferior understanding. Therefore, it is only through faith that one can truly recognize God. When intellect and other qualities accompany faith, it is like adding fragrance to gold, leaving no deficiency.

Furthermore, if one uses intellect first when approaching God or great individuals, it may be difficult to accept their actions. Even knowledgeable and wise individuals possess some level of faith. They are not entirely without faith, but they place their faith in other places rather than in God. As a result, like Parīkṣit, they struggle to accept God’s actions in their hearts.

Then Rojakā’s Kākābhāi asked what the signs are of nishchay without the greatness of God and nishchay (conviction) with the greatness of God. Mahārāj explained that nishchay without the greatness of God, no matter how much one maintains and cultivates it, leaves a feeling of incompleteness in the heart. Conversely, one who has nishchay with the greatness of God feels a sense of completeness and joy in their devotion, even if they face difficulties and are deprived of material comforts.

Kākābhāi then asked about the characteristics of the highest, middle, and lowest devotees. In response, Shriji Mahārāj explained that the highest devotee is one who, even after having the vision of the Supreme Self within their own self, still humbly considers the human form of God to be superior. A middle-level devotee is characterized by jealousy, and a lowest-level devotee is one who has greater affection for worldly matters.

Glossary

| Akshardham – The eternal supreme abode of Bhagwan Swaminarayan The divine realm where Bhagwan Swaminarayan resides along with Akshar Muktas (Divine Liberated Souls) |

| Bhrahmroop – A divine state attained by those fully immersed in God’s service. |

| Divine Form (Sakar) – The tangible, human-like form of God. |

| Divine lilas – God’s playful actions that appear worldly but have profound spiritual significance. |

| Gopis – Devotees of Lord Krishna renowned for their unconditional love and devotion. |

| Greatness of God – The acknowledgment of God’s infinite powers, divinity, and compassion. |

| Kama – The god of lust or desires, Desire for sensual pleasures, particularly related to women. |

| Nishtha – Dedication to living for and serving God and His devotees until death. |

| Ras Panchadhyayi lila – A divine play by Bhagwan Krishna with Gopis narrated in Shrimad Bhagwat Puran |

| Supreme Self – God’s divine presence within one’s self. |