Central Insights:

- The elimination of all desires except for God.

Key Points:

- By adhering to additional rules of renunciation related to the five sense objects and devotion to God, one develops desires exclusively for God while eliminating all others.

- Even if anger arises in the execution of a noble mission to guide countless souls towards God, it does not cause significant hindrance to that mission.

Explanation:

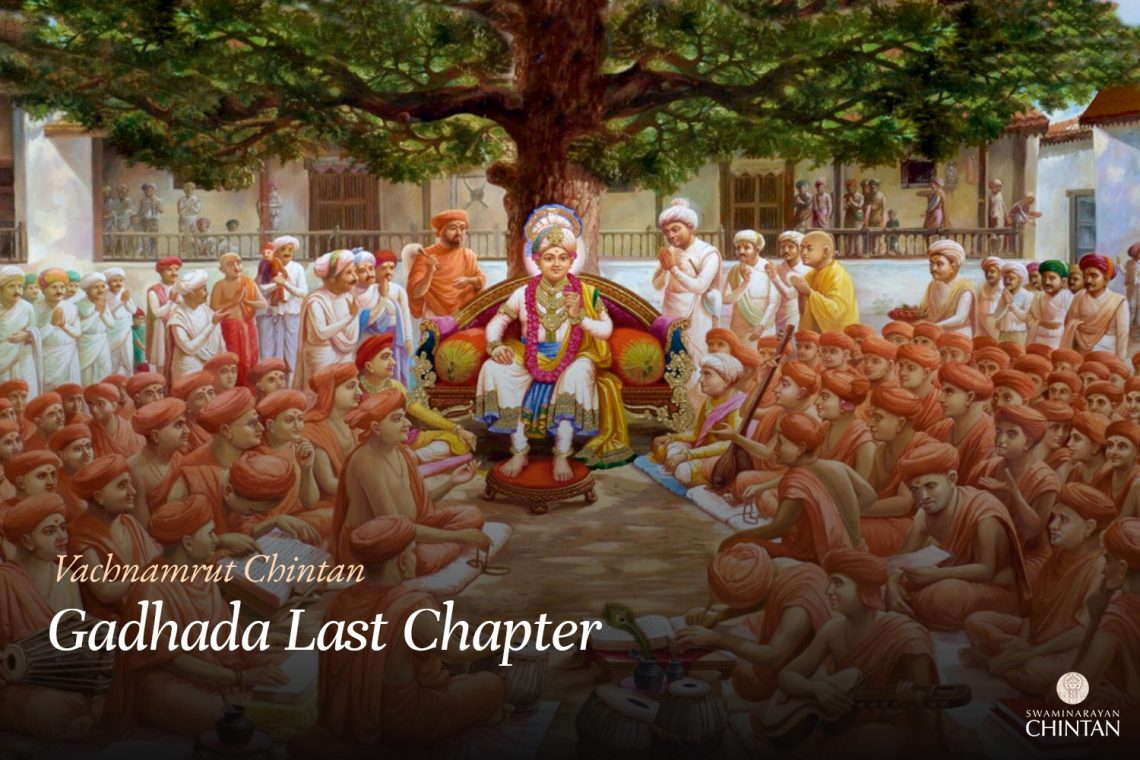

In this Vachanamrut, Shukmuni poses a question to Shreeji Maharaj: “How can one eliminate desires for all worldly objects and maintain desire solely for God?” Two means are mentioned: one is bhakti (devotion) toward God, and the other is vairagya (non-attachment) accompanied by gnan (knowledge). However, if these two means are not practiced intensely but one still has unwavering faith and conviction that “This present Shreeji Maharaj is the supreme avatari of all avatars, and having attained Him, my ultimate liberation is guaranteed,” then only minor worldly desires might arise due to insufficient vairagya.

To this, Shukmuni inquires further, asking if there exists any other method to eliminate worldly desires entirely, apart from the previously mentioned means.

Acknowledging the truth of this inquiry, Shreeji Maharaj responds by introducing a third method. This method ensures the eradication of all worldly desires, leaving only the desire for God. This involves strictly adhering to the rules prescribed by God for His devotees, especially regarding the renunciation of the five sense objects. For example, one must completely avoid all interaction with women (stri) in any of the eight forms and forsake engaging with pleasurable objects of the five senses. Even if one is not an atmanivedi bhakt (a devotee completely surrendered to God), one must still observe the rules related to surrender. Similarly, one must observe rules for devotion with great vigilance, ensuring that no moment passes without bhakti.

By following these rules diligently, a devotee’s heart begins to form auspicious resolves related to God. Desires associated with the world begin to diminish. Through such steadfast adherence, even within a short time, the devotee becomes spiritually strong, and all worldly desires are eradicated from the heart. Just as gnan and vairagya lead to the dissolution of desires, so do these diligently practiced rules. Hence, even if one lacks inherent gnan or vairagya, a sincere aspirant with a yearning for liberation can still observe these rules respectfully.

Moreover, Maharaj explains that adherence to rules enables victory over even the most intense senses, which vairagya alone may not conquer. Thus, the renunciation of the five sense objects and strict adherence to rules of devotion work as effectively as gnan and vairagya in purifying the heart of worldly desires, leaving only the desire for God.

Following this, Shukmuni asked another question: “Maharaj, anger arises when someone obstructs the attainment of an object one desires or to which one has formed attachment. When such a desire (kamna) is unfulfilled, it transforms into anger (krodh). As stated in the Gita, kamāt krodho’bhijāyate (from desire arises anger). Therefore, when the cause exists, anger inevitably arises. However, is there a way that anger does not arise at all, or if it does, can it exist without causing harm?”

The intent of Shukmuni’s question becomes clear through Maharaj’s reply. In Vachanamrut Loya 1, Maharaj describes anger as extremely detrimental, likening it to the saliva of a rabid dog and comparing it to the fear caused by serpents or tigers. Even in small amounts, anger is destructive. Hence, Shukmuni inquires whether, despite the presence of its cause, anger can either be prevented from arising or, if it does arise, exist without being harmful.

Maharaj responded that even if one’s desires are obstructed, it is possible for anger not to arise. Alternatively, if anger does arise, it may still be beneficial rather than harmful. Maharaj explained that if a seeker (mumukshu) has affection for a great sant and recognizes the sant as the cause of his ultimate welfare, believing firmly that “only through this sant will I attain my liberation,” then even if the seeker has a nature prone to anger, he will not direct his anger towards that sant. Instead, he will let go of his anger. In such cases, anger may arise, but it will not result in harm.

Maharaj further elaborates that great santo, acting on God’s commands or guided by scriptural insights, take up the noble task of keeping countless souls within the bounds of dharma and leading them on the path to God. They undertake this mission knowingly and with a pure intent. However, when someone violates the bounds of dharma and indulges in adharma, these great santo feel anger toward the transgressor because such actions disrupt their noble mission. This anger, when expressed to correct the transgressor, is justified. If they do not express anger and fail to admonish those who violate moral conduct, such violations would increase, and the well-being of countless souls would be jeopardized. Hence, anger in this context is appropriate and does not cause any harm; rather, it aids in fulfilling their auspicious intent.

Such santo often have thousands of people relying on them for their spiritual progress. Thus, how could they allow unchecked transgressions without reprimand? Only by renouncing their mission entirely could they avoid anger, but that is impossible, as they deeply understand the greatness of their task and the importance of obeying God’s commands. Consequently, even if anger arises, they do not abandon their noble mission. Such anger does not obstruct their efforts to lead others to God but rather serves as a tool to please God.

On the other hand, Maharaj emphasizes that if someone harbors anger toward a sant over trivial matters or for personal, petty reasons, it is evident that such a person has no understanding of the greatness of the sant or the significance of the path the sant represents. Even if that individual possesses intelligence, their behavior toward the sant reveals their intellect to be worldly, akin to that of a king’s servant, with no comprehension of the spiritual path or the ultimate goal.

Glossary

| Vairagya – Detachment From Everything Except God |

| Gyan – Knowledge |

| Bhakti – Devotion Loving and selfless worship of God. |

| Atmanivedi Bhakt – Fully surrendered devotee A devotee who has completely surrendered to Bhagwan, prioritizing Him above all else. |

| Panch Vishay – Five sensory objects |

| Seva – Service Selfless service rendered to God and His devotees. |

| Krodh – Anger |

| Mumukshu – Seeker of liberation (Moksha) |

| Nishkam Karmayoga – Selfless action without desire for reward |

| Satsang – Holy fellowship |

| Mahima – The understanding of Bhagwan’s supreme glory, inspiring steadfast devotion and loyalty. |

| Dharmamaryada – Moral boundaries The ethical limits prescribed by God and scriptures. |

| Krodh Yukti – Strategic anger Anger used purposefully by saints to correct transgressions and protect dharma, not arising from ego. |

| Atmasambandhi Niyam – Rules related to personal conduct Spiritual disciplines and observances prescribed for one’s personal spiritual progress. |