Central Insights:

- The flaws of a renunciate.

Key Points:

- For a renunciate, harboring sambandhi (familial attachment) or kamna (worldly desires) are major defects.

- Excessive affection for one’s sevak (servant or helper) should also be avoided.

Explanation:

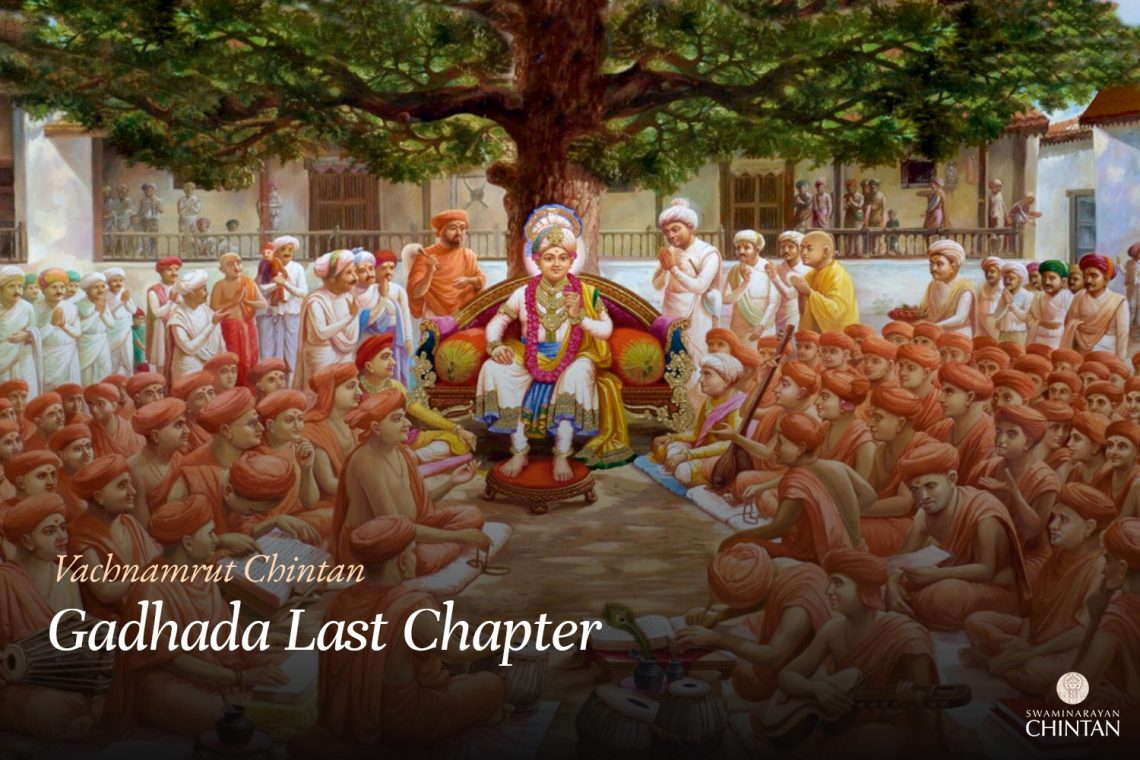

This Vachanamrut addresses the defects of a renunciate. Maharaj explains that a renunciate (tyagi) who has renounced the world may possess two flaws that diminish the glory of Satsang (holy fellowship) and tarnish its reputation. These two flaws are kamna (worldly desires) and prit (affection) toward one’s family. Maharaj emphasizes that a renunciate with these traits appears to Him like an animal. Animals exhibit affection toward their offspring and vice versa, without any reasoning or thought. Among humans, especially householders, such affection often has a rational basis, such as expecting care during old age or passing down inheritance. However, animals do not think along such lines. Maharaj questions the rationale behind a renunciate harboring familial affection, as no valid reasoning or justification seems apparent—it appears merely as instinctual behavior akin to that of animals, which is a blemish on the renunciate’s path.

Here, the term kamna does not refer to desiring the fruits of one’s actions, but rather specifically to the desire for sensual pleasures. Maharaj states that a renunciate with affection for their family brings great dishonor. Such attachment is regarded as a sin greater than the panch-mahapap (five grave sins). Therefore, a renunciate must perceive themselves as separate from their body and bodily relations, considering all relatives as equivalent to those from the 8.4 million (84 lakh) life cycles. Even if one’s relatives are Satsangis (devotees of God), affection toward them should not develop. If such affection arises, the familial bond takes precedence, and the spiritual connection becomes secondary. Over time, this leads to degeneration, as illustrated by Maharaj through the metaphor of impurities surfacing while clarifying butter into ghee—ultimately, these impurities spoil the final product. Similarly, at the moment of death, any latent weakness in the soul manifests, obstructing remembrance of God, leading to a poor rebirth. Maharaj provides the example of King Bharat, who, despite his spiritual greatness, was reborn as a deer due to his attachment to a fawn.

Maharaj also warns that even if a sevak (servant) rendering service is a devotee, a renunciate should avoid developing affection toward them. Such attachment, even for a devotee, becomes a significant impediment to liberation (moksha). Maharaj compares it to serpent saliva, which turns milk poisonous; similarly, selfish affection for those who serve becomes an obstacle in worship and devotion to God. Therefore, a renunciate must remain vigilant against these three defects: familial affection, worldly desires, and excessive attachment to a servant. Among these, kamna is the greatest blemish as a vice, while affection for a sevak is not considered a fault in worldly life but is a critical pitfall on the path to moksha. Familial affection, however, directly contradicts the renunciate’s foundational principles and the eternal Sanatan Dharma. Hence, it is deemed a sin.

Maharaj explains this with an analogy: Just as traffic laws differ between countries (e.g., driving on the left in India versus the right in the USA), what is permissible in one situation (householder life) may become a fault in another (renunciate life). For householders, revering and serving parents is a duty; for renunciates, the same action becomes sinful. The scriptures define merit and sin according to specific contexts, and such rules are not always reconcilable with human reasoning. A renunciate must therefore accept these principles with vigilance, as they stem from a divine perspective.

To ensure renunciates remember these three critical principles—avoidance of familial affection, worldly desires, and attachment to servants—Maharaj instructs that senior members in assemblies should daily remind junior renunciates of these guidelines. Maharaj further mandates fasting on days when this instruction is not adhered to.

Some may misinterpret Maharaj’s instructions as reinforcing familial affection, given the daily reminders. However, Maharaj clarifies that the purpose of these reminders is to reinforce the renunciate’s constitution and spiritual guidelines—not to refresh affection for family ties.

Thus, Maharaj’s daily reminders emphasize adherence to the renunciate code, making these principles vivid and preventing any lapse in vigilance.

Glossary

| Kamna – Desire for sensual pleasures |

| Prit – Affection Refers to attachment, especially familial, which is considered a fault in the path of renunciation. |

| Sevak – Servant or helper One who serves a sant or devotee. Excessive affection toward such a person can become a spiritual obstacle for a renunciate. |

| Panch-mahapap – Five grave sins Refers to major sins in Hindu dharma, including Brahmahatya (killing a Brahmin), Sura-paana (drinking intoxicants), Asteya (stealing gold), Guru-patni-gamana (adultery with the wife of a spiritual teacher), and associating with those who commit these sins. Maharaj considers familial affection worse than these for a renunciate. |

| Sanatan Dharma – Eternal spiritual tradition The original, unchanging path of dharma. Familial affection contradicts this tradition for renunciates. |

| Moksha – Salvation |

| Tyagi – Renunciant |

| Ghee Analogy – Clarification metaphor for inner impurities Just as impurities rise and spoil ghee during clarification, latent desires or attachments spoil the soul’s spiritual purity, especially at the time of death. |